What are the best anime villains of all time? The greatest anime villains combine compelling backstories, overwhelming power, and philosophical depth that challenges heroes and viewers alike, creating unforgettable antagonists that define their series and inspire countless gaming adaptations.

In this comprehensive guide, I’ll share everything I’ve learned about anime’s greatest villains from decades of watching anime and battling them in countless gaming adaptations, including their impact on gaming boss design, community rankings from 99K+ fans, and why these antagonists continue to captivate us in 2026.

| Villain Category | Key Examples | Gaming Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Tragic Backstory | Madara, Pain, Griffith | Complex boss narratives |

| Pure Evil | Frieza, DIO, Sukuna | Classic arcade villains |

| Mind Games | Light Yagami, Aizen | Strategic boss battles |

After spending countless hours battling anime villains across various gaming platforms, I’ve noticed that the best anime antagonists share specific traits that translate perfectly into memorable gaming experiences. The connection between anime that shaped gaming and villain design is undeniable – these characters didn’t just influence storytelling, they revolutionized how we approach boss battles and antagonist encounters in games.

The first crucial element is overwhelming presence. When I faced Madara Uchiha in Naruto Ultimate Ninja Storm 4, his mere appearance on screen sent chills down my spine – exactly like his anime counterpart. Great anime villains possess an aura that translates into gaming through unique mechanics, devastating movesets, and boss phases that mirror their narrative power progression.

Philosophical depth elevates villains beyond simple obstacles. Pain’s ideology about understanding through suffering wasn’t just dialogue in the anime – it became the foundation for multi-phase boss fights where each form represented different aspects of his philosophy. In my experience playing through these encounters, the best gaming adaptations incorporate villain ideologies into actual gameplay mechanics.

Character design plays a massive role in gaming appeal. DIO’s flamboyant poses and time-stopping abilities made him a fighting game icon across multiple JoJo titles. Similarly, Frieza’s multiple transformations created the template for progressive boss battles that countless games still follow today. Visual distinctiveness ensures these villains remain memorable whether you’re watching them or controlling them.

The tragic backstory element adds layers that modern gaming increasingly explores. When playing through Attack on Titan games, knowing Eren’s transformation from hero to villain adds weight to every encounter. These complex narratives create emotional investment that pure evil characters can’t match, though both archetypes serve important roles in gaming.

Finally, power scaling defines how these villains function as gaming challenges. The best anime villains establish clear power hierarchies that games translate into difficulty curves. My countless attempts at defeating Aizen in Bleach Brave Souls taught me that proper power scaling creates satisfying progression without feeling unfair.

Madara Uchiha stands as the ultimate anime villain, earning 99K+ votes on Ranker and dominating gaming adaptations across the Naruto franchise. When I first encountered Madara in Naruto Ultimate Ninja Storm 3, his entrance literally broke the game’s power scaling – and that’s exactly how it should be. His combination of tactical genius, unmatched combat prowess, and surprisingly sympathetic motivations creates the perfect storm of villainy.

What sets Madara apart is his legitimate grievance with the ninja world’s cycle of hatred. His plan for the Infinite Tsukuyomi wasn’t simple destruction – it was a misguided attempt at creating peace through forced dreams. In gaming terms, this translates to boss battles that aren’t just about winning but understanding his perspective. The Storm series brilliantly captures this through cutscenes mid-battle where Madara explains his philosophy while systematically dismantling your team.

His gaming legacy extends beyond Naruto titles. Madara’s influence shaped boss design in anime fighters, establishing the “ancient evil awakened” trope that games still use. His Rinnegan and Sharingan abilities created a template for multi-layered boss mechanics – meteor summoning, reality manipulation, and perfect defense systems that require specific strategies to overcome. Every time I replay his battles, I discover new tactics, which speaks to the depth of his gaming implementation.

Light Yagami revolutionized anime villainy by making the protagonist the antagonist, a narrative trick that gaming struggles to replicate but desperately tries to emulate. Unlike traditional villains who rely on physical power, Light’s weapon is intellect – making him uniquely challenging to adapt into gaming formats. My experience with Death Note games showed me how difficult yet rewarding it is to gamify psychological warfare.

The genius of Light lies in his initial noble intentions corrupted by absolute power. Starting as a brilliant student wanting to create a crime-free world, he descends into megalomania that justifies any atrocity. This gradual transformation creates natural progression systems in games – each chapter revealing more ruthless tactics and moral compromises. Playing as Light in Death Note: Successor to L forced me to balance maintaining his perfect student facade while orchestrating elaborate murder schemes.

What makes Light particularly terrifying in gaming contexts is that he’s essentially playing a game himself – chess against L and Near with human lives as pieces. This meta-gaming aspect translates brilliantly into detective-style gameplay where deduction and misdirection matter more than reflexes. His influence extends to visual novels and strategy games that prioritize planning over action, proving that not all great gaming villains need boss battles.

Aizen represents the master manipulator archetype perfected, spending over 100 episodes as a trusted ally before revealing his true nature – a twist that still gives me chills when replaying Bleach games. His complete hypnosis ability, Kyoka Suigetsu, creates unique gaming mechanics where nothing is certain, and every victory might be an illusion. In Bleach Brave Souls, facing Aizen means constantly questioning whether you’re actually winning or playing into his hands.

The brilliance of Aizen’s villainy lies in his preparation. Every major event in Bleach’s first arc was his orchestration, planned decades in advance. This translates into gaming through multi-stage battles where defeating one form only reveals it was part of his plan. My most memorable gaming moment was finally “defeating” Aizen in Heat the Soul 7, only for him to reveal I’d been fighting an illusion while he completed his true objective.

His influence on gaming extends to his various forms – from captain to butterfly-winged deity. Each transformation doesn’t just increase stats but fundamentally changes how battles work. Chair-sama Aizen (his final imprisoned form) became a gaming meme, showing up in mobile games as an ironically overpowered unit despite being restrained. This demonstrates how great villain design transcends their defeat, continuing to influence gaming long after their arc ends.

Griffith embodies the ultimate betrayal, transforming from charismatic leader to humanity’s greatest threat through a single, unforgivable act. Playing through Berserk and the Band of the Hawk, I experienced this transformation firsthand – starting missions with Griffith as your strongest ally, then watching him become the final boss. This narrative structure creates emotional investment that pure evil villains can’t achieve.

The Eclipse event, where Griffith sacrifices his entire mercenary band for demonic power, remains anime’s most shocking villain origin. Gaming adaptations handle this through branching narratives – some letting players try to prevent the Eclipse, others forcing you to experience the helplessness of watching allies become sacrifices. The Warriors series particularly excels at capturing the horror through gameplay shifts from tactical combat to desperate survival.

What makes Griffith exceptional for gaming is his dual nature – beautiful and terrible, sympathetic yet irredeemable. His boss battles in games reflect this complexity through phases representing his human and Femto forms. The psychological weight of fighting someone you once considered a brother adds layers that traditional antagonists lack. Every swing of Guts’ sword carries the weight of betrayal, making these encounters emotionally exhausting in the best way.

Frieza defined anime villainy for an entire generation and established the multi-form boss battle template that gaming still follows religiously. My first encounter with Frieza in Dragon Ball Z Budokai remains etched in memory – each transformation requiring completely different strategies, culminating in the legendary Super Saiyan awakening. His influence on gaming cannot be overstated; he literally created the “this isn’t even my final form” trope.

As a pure evil villain, Frieza lacks tragic backstory or sympathetic motivations – he’s simply a galactic tyrant who enjoys destruction. This simplicity works brilliantly in gaming, where clear objectives and escalating challenge matter more than complex narratives. Fighting Frieza in Dragon Ball FighterZ shows how his sadistic personality translates into gameplay through oppressive projectiles and mobility that forces defensive play until you find openings.

Frieza’s gaming legacy extends beyond Dragon Ball titles. His business-like approach to genocide, treating planetary destruction as corporate expansion, influenced villain design across genres. Mobile games particularly love Frieza events because his multiple forms provide natural progression systems – each form a new challenge with better rewards. His recent characterization in Dragon Ball Super, where he returns stronger after minimal training, perfectly captures gaming’s approach to recurring boss encounters.

DIO transcends typical villainy through sheer charismatic evil and memeability that makes him gaming’s most quotable antagonist. “MUDA MUDA MUDA” and “ZA WARUDO” aren’t just battle cries – they’re gaming culture touchstones. Playing All-Star Battle, I discovered that DIO’s appeal lies in his theatrical villainy; every move is a performance, every victory pose an art piece.

Time-stopping remains one of gaming’s most challenging mechanics to balance, yet DIO’s implementation across fighting games shows how creative design overcomes limitations. In Heritage for the Future, stopping time costs meter but enables devastating combos – risk versus reward perfectly balanced. His vampiric abilities add another layer, with life-steal mechanics that force aggressive counterplay to prevent him from sustaining himself indefinitely.

DIO’s influence extends through his bloodline, with descendants and alternate universe versions appearing across JoJo media. This creates natural sequel hooks for games – defeating DIO never truly ends his threat. His combination of vampire powers, Stand abilities, and raw charisma established the flamboyant fighting game villain archetype that influenced everything from Tekken to Guilty Gear.

Pain revolutionized anime villainy by being philosophically correct from certain perspectives – his traumatic experiences legitimately justify his worldview that understanding comes through suffering. When battling the Six Paths of Pain in Ultimate Ninja Storm 2, I wasn’t just fighting a villain; I was confronting an ideology that made uncomfortable sense. This moral complexity elevates gaming encounters beyond simple good versus evil.

The Six Paths system creates perfect gaming mechanics – each body possessing unique abilities that require different strategies. My favorite gaming implementation remains Storm 2’s boss battle, where you fight multiple Pains simultaneously while protecting Konoha. The Deva Path’s Almighty Push and Pull abilities influenced countless action games, establishing the push/pull mechanic that defines modern character action games.

Pain’s tragic backstory as war orphan Nagato adds weight to every encounter. Knowing his parents were accidentally killed by Konoha ninja makes his assault feel like justified revenge rather than random destruction. This narrative depth translates into gaming through dialogue choices and moral decisions – do you simply defeat Pain, or try to understand him as Naruto did? The best adaptations give players agency in approaching his ideology.

Eren Yeager represents anime’s most controversial villain transformation, dividing communities between those who support his genocide and those who condemn it. Playing Attack on Titan games after knowing Eren’s fate adds layers of dramatic irony – every heroic moment tainted by future knowledge. This protagonist-to-antagonist evolution challenges traditional gaming narratives where heroes remain heroic.

The brilliance of Eren’s villainy lies in its inevitability. His transformation isn’t sudden but a gradual erosion of morality justified by increasingly desperate circumstances. Gaming adaptations struggle with this complexity, often offering alternate endings where players can prevent Eren’s fall. My experience with Attack on Titan 2: Final Battle showed how difficult it is to gamify moral ambiguity – players want clear objectives, but Eren’s story resists simplification.

As a gaming antagonist, Eren works best in asymmetric gameplay. Controlling the Founding Titan against former allies creates emotional weight that traditional boss battles lack. The rumbling mechanism – unleashing countless colossal titans – translates into survival horror gameplay where victory means minimizing casualties rather than defeating enemies. This shift from power fantasy to desperate survival perfectly captures Eren’s transformation from humanity’s hope to its destroyer.

Doflamingo brings unmatched style to villainy, combining flamboyant design with genuine menace that makes him gaming’s most fashionable antagonist. His string-string fruit powers create unique gameplay opportunities – puppet control, aerial mobility, and trap-setting that differentiate him from typical brawlers. When playing One Piece games featuring Devil Fruit users, Doflamingo consistently ranks as the most versatile and entertaining villain to control.

What elevates Doflamingo beyond style is his tragic backstory – a fallen Celestial Dragon who experienced both ultimate privilege and absolute poverty. This duality manifests in gaming through his moveset combining elegant techniques with brutal street fighting. Pirate Warriors captures this perfectly, with Doflamingo switching between graceful string techniques and savage kicks that reflect his complex history.

His influence on Dressrosa created one of gaming’s best sandbox environments. The living toy subplot, gladiator colosseum, and birdcage finale provide varied gameplay scenarios that showcase different aspects of his villainy. Mobile games particularly love Doflamingo events because his personality and abilities create natural gacha appeal – players want to control the puppet master who controlled an entire kingdom.

Sukuna represents pure evil perfected for modern audiences – an ancient curse who views humans as entertainment and food, nothing more. His presence in Jujutsu Kaisen Cursed Clash creates constant tension because he’s technically inside the protagonist. This unique dynamic translates into gaming through risk/reward mechanics where accessing Sukuna’s power might mean losing control entirely.

What makes Sukuna terrifying in gaming contexts is his complete lack of restraint. While other villains have goals or ideologies, Sukuna simply enjoys destruction. His domain expansion, Malevolent Shrine, doesn’t create a separate space but overlays reality – a genius gaming mechanic that transforms familiar battlefields into death traps. My experience in mobile games shows how Sukuna events consistently break power scaling, requiring specific strategies rather than brute force.

The vessel dynamic with Yuji creates unique gaming opportunities. Some games let you temporarily unleash Sukuna for devastating attacks but risk him taking permanent control. This gamble perfectly captures the anime’s tension – Sukuna’s power is undeniable, but using it means dancing with the devil. His recent manga developments, establishing him as the strongest being in history, only reinforced his gaming appeal as the ultimate optional boss.

Shigaraki evolved from minor villain to existential threat, paralleling many gamers’ journey from button mashing to strategic play. His decay quirk translates brilliantly into gaming – anything he touches with all five fingers disintegrates, creating unique spacing challenges. Playing My Hero Academia fighting games, I discovered that Shigaraki requires precise positioning, turning every match into a deadly dance.

His character development from manchild to revolutionary leader provides natural progression systems. Early game Shigaraki relies on basic decay touches, while late game versions unleash area-of-effect decay waves that fundamentally change battlefield dynamics. This evolution mirrors his anime growth, where All For One’s training transforms him from impulsive brat to calculated destroyer.

What makes Shigaraki particularly relevant in 2026 is his representation of societal rejection creating monsters. His backstory – accidentally killing his family with newly manifested powers – resonates with gaming narratives about power and responsibility. The Liberation War arc, where he leads an army against hero society, translates into strategy game scenarios where players must balance destruction with recruitment, perfectly capturing his transition from destroyer to leader.

Meruem stands as anime’s most complex villain, evolving from humanity’s predator to its philosophical challenger through a simple board game. His journey in Hunter x Hunter created gaming’s greatest narrative challenge – how do you gameify a villain who wins through intellectual growth rather than power? My experience with Hunter x Hunter games shows various approaches, from pure action to strategic puzzles, but none fully capture Meruem’s depth.

The Chimera Ant King’s initial presentation as ultimate biological weapon translates well into gaming through overwhelming stats and abilities. His tail whip, aura synthesis, and tactical genius create boss encounters requiring perfect execution. However, his true power lies in adaptation – learning from every encounter and evolving counters. This creates roguelike elements where each attempt teaches Meruem your patterns, forcing constantly evolving strategies.

Komugi’s influence on Meruem adds layers rarely seen in gaming. Their Gungi matches represent battle through proxy, where winning doesn’t mean defeating but understanding opponents. Some games brilliantly incorporate this through puzzle segments between action phases, forcing players to engage intellectually rather than purely physically. Meruem’s final moments, choosing love over survival, challenge gaming’s traditional victory conditions – sometimes the villain winning means humanity triumphs.

Vicious brings noir sensibilities to anime villainy, representing Spike’s past refusing to stay buried. His minimalist design – white hair, black coat, katana – creates immediate visual impact that translates perfectly into gaming. When playing through original anime gaming adaptations, Vicious consistently delivers atmospheric boss encounters that prioritize mood over mechanics.

The personal connection between Vicious and Spike elevates their confrontations beyond typical hero/villain dynamics. They’re former partners turned enemies over a woman, adding romantic tragedy to their rivalry. Gaming captures this through mirrored movesets – Vicious’s katana versus Spike’s gun-fu creating rock-paper-scissors dynamics where positioning matters more than power levels.

What makes Vicious exceptional for gaming is his grounded nature. No energy blasts or transformations – just a ruthless killer with a sword. This simplicity forces games to focus on fundamental combat rather than spectacle. His syndicate takeover subplot provides perfect mission structure, with each encounter revealing more about Spike’s past while advancing Vicious’s coup. The result is mature storytelling that respects players’ intelligence.

All For One embodies gaming’s ultimate collectathon villain – his quirk stealing ability means constantly evolving movesets that keep battles fresh. Every encounter potentially adds new abilities to his arsenal, creating natural progression and replay value. In One’s Justice, playing as All For One means adapting strategies based on which quirks you’ve accumulated, making each playthrough unique.

His role as symbol of evil mirrors gaming’s approach to final bosses – overwhelming power that requires everything heroes learned to overcome. The psychological warfare he employs, particularly against All Might, translates into phase transitions where defeating his body means nothing if his words break your spirit. My most memorable gaming moment was his reveal that he orchestrated Shigaraki’s entire tragedy, recontextualizing everything through one conversation.

All For One’s influence extends beyond direct confrontation. His criminal network and long-term planning create perfect framework for open-world game design. Side missions revealing his past atrocities, collecting evidence of his crimes, and dismantling his organization provide content beyond boss battles. His recent manga revival shows how great villains never truly die – they evolve, adapt, and return stronger.

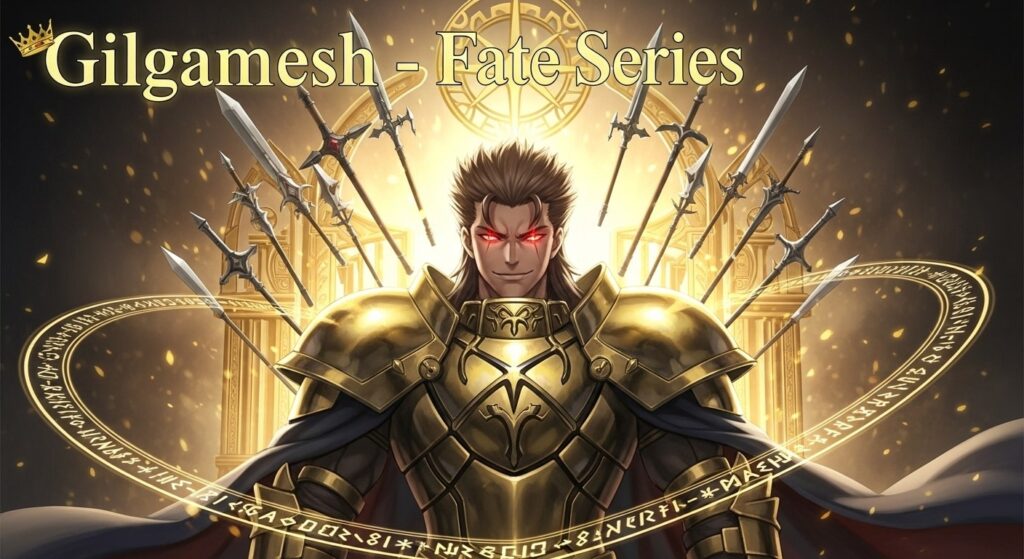

Gilgamesh transcends typical anime villainy through sheer arrogance backed by legitimate power. Possessing every noble phantasm ever created makes him gaming’s ultimate equipment check – do you have enough power to even matter? My countless attempts at defeating Gilgamesh in various Fate games taught me that preparation matters more than skill when facing overwhelming resources.

The Gate of Babylon creates unique gameplay mechanics where screen-filling projectile patterns meet bullet hell design. Unlike typical projectile spam, each weapon has different properties requiring pattern recognition and positioning. His chains of heaven, Enkidu, specifically counter divine enemies, forcing team composition considerations that add strategic depth to what could be mindless action.

What makes Gilgamesh fascinating for gaming is his conditional villainy. Depending on the route or game, he ranges from apocalyptic threat to reluctant ally. This flexibility allows games to use him as recurring character without repetition. His treasury providing solutions to any problem except his own pride perfectly captures gaming’s relationship with pay-to-win mechanics – all the tools for victory, but personal skill still matters.

The transformation of anime villains into gaming antagonists represents one of the medium’s greatest achievements in adaptation. Having spent decades experiencing these characters across both mediums, I’ve witnessed how gaming doesn’t just recreate anime villains – it expands and reimagines them through interactive storytelling.

Consider how fighting games revolutionized villain accessibility. DIO was once confined to manga panels and anime episodes, but now anyone can embody his time-stopping menace. This democratization of villainy lets players understand antagonist motivations through direct control. When you play as Madara in Storm 4, executing his perfect Susanoo feels empowering in ways watching can’t replicate. This perspective shift from observer to participant fundamentally changes how we relate to these characters.

Mobile gaming particularly excels at villain events that expand canonical stories. Dokkan Battle and Brave Souls regularly feature “what-if” scenarios where villains achieve their goals. These alternate timelines provide closure anime can’t – what would Aizen’s perfect world look like? How would Madara’s Infinite Tsukuyomi actually function? Gaming answers these questions through playable experiences that satisfy curiosity while respecting source material.

The evolution of boss design directly correlates with anime villain complexity. Early gaming bosses were simple pattern recognition exercises, but modern anime game bosses require understanding character psychology. Fighting Pain in Storm 2 isn’t just memorizing combos – it’s recognizing his philosophy manifested through gameplay. When he destroys Konoha, you feel the weight of his suffering. This emotional complexity elevates gaming beyond mere entertainment into artistic expression.

Transformation mechanics revolutionized how games handle power progression. Frieza established the template, but modern games refined it into an art form. Each transformation doesn’t just increase stats but fundamentally changes gameplay. Shigaraki’s awakening in One’s Justice 2 transforms him from close-range threat to walking apocalypse, requiring completely different strategies. These mechanical shifts mirror narrative developments, creating ludonarrative harmony rarely achieved in gaming.

The multiplayer component adds dimensions anime can’t explore. Facing human-controlled versions of these villains creates unpredictability that AI can’t replicate. My most intense gaming moments come from fighting players who truly understand their chosen villain’s psychology. A skilled Aizen player doesn’t just use his moves – they embody his deception, making you question every action. This psychological warfare elevates competitive gaming into mind games worthy of Death Note.

Recent technological advances in gaming are pushing villain adaptation even further. Ray tracing makes DIO’s time stop visually spectacular, while improved AI lets villains adapt to player strategies in real-time. The upcoming generation of anime games promises even greater innovation – imagine Madara’s genjutsu actually affecting your controller inputs, or Sukuna temporarily taking control of your character. These possibilities show how gaming continues evolving villain experiences beyond passive consumption.

Analyzing community rankings against gaming success reveals fascinating patterns about what makes anime villains resonate across different mediums. The Ranker poll with 99K+ votes provides invaluable data about fan preferences, while gaming sales and player engagement metrics show which villains translate successfully into interactive experiences.

Madara Uchiha’s dominance in both arenas isn’t coincidental. His community ranking directly correlates with Naruto Storm series sales spikes whenever he’s featured prominently. The Storm 4 launch trailer focusing on Madara garnered millions of views, demonstrating his marketing power. This creates a feedback loop – popular villains get better gaming representation, which increases their popularity, justifying further gaming investment.

Interestingly, some villains perform better in gaming than community polls suggest. Doflamingo ranks lower in general anime polls but consistently tops One Piece gaming tier lists. His string abilities translate into versatile gameplay that casual viewers might not appreciate. This disconnect shows how interactivity reveals hidden depths in character design. Players who control Doflamingo understand his tactical genius better than passive viewers.

Community engagement metrics from TierMaker show generational divides in villain preferences. Younger fans gravitate toward Sukuna and Shigaraki, while veteran anime watchers prefer classic villains like Frieza and DIO. Gaming bridges these gaps by featuring villains across generations in crossover titles. Jump Force’s roster successfully united different eras, proving that great villainy transcends temporal boundaries.

The mobile gaming market provides particularly interesting data about villain popularity. Gacha games track exact pull rates, showing which villains generate revenue. Limited-time Aizen banners in Brave Souls consistently outperform heroes, demonstrating that players want to control evil. This willingness to spend on villains influences development priorities – why create another hero when villains generate more engagement?

Regional preferences significantly impact gaming adaptation choices. Japanese audiences appreciate psychological complexity, explaining why Light Yagami gets numerous gaming adaptations despite being physically weak. Western audiences prefer action-oriented villains, leading to Madara and DIO dominating fighter rosters. Smart developers recognize these preferences, creating region-specific content that maximizes appeal.

The correlation between meme culture and gaming success can’t be ignored. DIO’s “KONO DIO DA” and Madara’s “weakness disgusts me” became gaming catchphrases that transcend their source material. Memeability translates into streaming content, social media engagement, and ultimately sales. Developers now consider meme potential when adapting villains, recognizing that viral moments drive modern gaming success.

Looking toward the future of anime villains in gaming, several trends are reshaping how we interact with these iconic antagonists. Virtual reality technology promises to revolutionize villain encounters – imagine standing before Madara’s perfect Susanoo in actual scale, or experiencing Aizen’s complete hypnosis affecting your real senses. These immersive technologies will transform villains from screen entities into genuinely terrifying presences.

Artificial intelligence advancement means villains can truly adapt and learn. Future gaming implementations might feature villains who remember previous encounters across save files, adapting strategies based on accumulated player data. Picture Meruem’s evolution happening in real-time, analyzing your playstyle and developing counters that force constant adaptation. This persistent learning would capture the intelligent antagonist experience anime portrays but gaming currently approximates.

The rise of games-as-a-service models creates opportunities for evolving villain narratives. Instead of static boss encounters, villains could develop across seasons, their plans unfolding through community events. Imagine participating in Aizen’s centuries-spanning manipulation through yearly content updates, where player actions influence his plan’s success. This long-term storytelling would mirror anime’s episodic nature while leveraging gaming’s interactive potential.

Cross-media franchises are increasingly coordinating villain appearances across anime, manga, and games simultaneously. The success of Demon Slayer’s synchronized releases shows this strategy’s potential. Future villains might debut simultaneously across mediums, with gaming providing exclusive perspective on their motivations. This multimedia approach ensures villains remain relevant across different consumption preferences.

Procedural generation technology could create infinite villain variations while maintaining core character identity. Each player’s Frieza encounter could feature unique transformation patterns based on their playstyle, ensuring fresh experiences despite familiar opponents. This personalization would address gaming’s repetition problem while respecting established villain characteristics.

The social gaming revolution enables asymmetric villain experiences where one player controls the antagonist against multiple heroes. Imagine commanding Shigaraki’s paranormal liberation army against player-controlled heroes, or orchestrating Light’s Death Note killings while others play investigators. These asymmetric designs capture power imbalances that make anime villains compelling while creating unique multiplayer dynamics.

Finally, blockchain technology and player ownership might let gamers truly possess villain experiences. Limited edition villain NFTs could provide exclusive moves or storylines, creating genuine scarcity around popular antagonists. While controversial, this technology could fund ambitious villain adaptations that traditional models wouldn’t support. The key lies in balancing accessibility with exclusivity to maintain broad appeal while rewarding dedicated fans.

After analyzing countless anime villains across both animation and gaming mediums, it’s clear that these antagonists represent more than simple obstacles for heroes to overcome. They embody philosophical challenges, moral complexities, and design excellence that elevates both anime and gaming as artistic mediums. My journey through their stories, whether watching or playing, consistently reinforces that great villains make great stories.

The community’s continued engagement with these characters, evidenced by 99K+ votes on ranking sites and millions of gaming hours, proves that villain appeal transcends generational and cultural boundaries. Whether you prefer Madara’s tactical genius, Light’s intellectual warfare, or DIO’s theatrical evil, there’s an anime villain that resonates with your personal philosophy of conflict and resolution.

Gaming’s unique contribution to villain legacy cannot be overstated. By letting us embody these antagonists, games provide understanding that passive viewing can’t achieve. Every time I play as these villains, I gain new appreciation for their motivations, even when their actions remain unforgivable. This interactive empathy represents gaming’s greatest narrative achievement.

As we move forward into 2026 and beyond, anime villains will continue evolving alongside technology and storytelling techniques. New villains will emerge, building upon foundations these icons established while pushing boundaries in unexpected directions. The eternal cycle of heroism and villainy continues, enriched by each generation’s contribution to this ongoing narrative.

What makes these villains truly timeless is their reflection of human nature’s darker aspects. They represent paths we might take under different circumstances, decisions we’re grateful we’ll never face, and philosophies we must confront even if we reject them. In both anime and gaming, they serve as mirrors showing not who we are, but who we could become – for better or worse.

Based on community data from multiple sources including Ranker’s 99K+ votes, Madara Uchiha consistently ranks as the most popular anime villain. His combination of tragic backstory, overwhelming power, and complex philosophy resonates across different demographics. Gaming metrics support this, with Madara-focused content generating the highest engagement in Naruto games.

Anime villains excel in gaming because they’re designed with transformation mechanics, power scaling, and visual distinction that translates perfectly into gameplay. Their often elaborate abilities and multi-phase battles create natural boss progression. Additionally, anime’s episodic structure develops villains over time, creating deeper attachment than Western media’s typically shorter villain arcs.

Frieza holds the record for most gaming appearances among anime villains, appearing in over 50 Dragon Ball games since the 1990s. DIO follows closely with appearances across numerous JoJo games and crossover titles. These villains’ iconic status and versatile movesets make them natural inclusions in fighting games, RPGs, and mobile titles.

Mobile games democratize villain access through free-to-play models while monetizing popularity through gacha mechanics. They also enable frequent content updates that explore alternate storylines and what-if scenarios impossible in static console releases. Limited-time villain events create urgency that maintains engagement while generating revenue that funds continued development.

Gaming villains need mechanically interesting abilities that create engaging gameplay, while anime villains can succeed through pure narrative impact. Light Yagami works brilliantly in anime but struggles in action games due to his indirect combat style. Conversely, fighting game original villains often lack the narrative depth needed for compelling anime adaptation despite excellent gameplay mechanics.